'If the heart of one friend is open to another, the truth glows between them, the good enfolds them, and each becomes a mainstay to his companion, a helpmate in his endeavor, and a potent factor in his attaining his wish. There is nothing surprising in this: souls ignite one another, minds fertilize one another, tongues exchange confidences; and the mysteries of this human being, a microcosm in this macrocosm, abound and spread.' [1]

That is the 10th-century Islamic philosopher Abu Sulayman al-Sijistani--who, like Socrates, 'wrote little or nothing himself' [2]--speaking to his disciples in the Muqabasat, or 'Borrowings', of Abu'l-Hayyan al-Tawhidi, quoted from an excerpt of Joel L. Kraemer's Humanism in the Renaissance of Islam found in Night & Horses & the Desert: An Anthology of Classical Arabic Literature, edited by Robert Irwin.

It's a powerful classical conception of friendship, on which of course there is a tradition of philosophy beginning with the ancient Greeks, particularly Aristotle, and running through Cicero, and finding beautiful Christian treatments in St John Cassian's Conferences and Aelred of Rievaulx's Spiritual Friendship. Since this is only a marginalium and not a proper post, I won't go to the trouble of walking downstairs and finding my new volume on Islamic philosophy to see if there are any comments on these figures in there. But I will note that Irwin writes: 'Tawhidi and his teachers and friends were interested in Greek philosophy and Sufism, and in reconciling Sufism with Neoplatonism.' [175] I suppose then that it is at least very likely that Abu Sulayman would have been familiar with Aristotle's thoughts on the subject of friendship, whatever else he may have read.

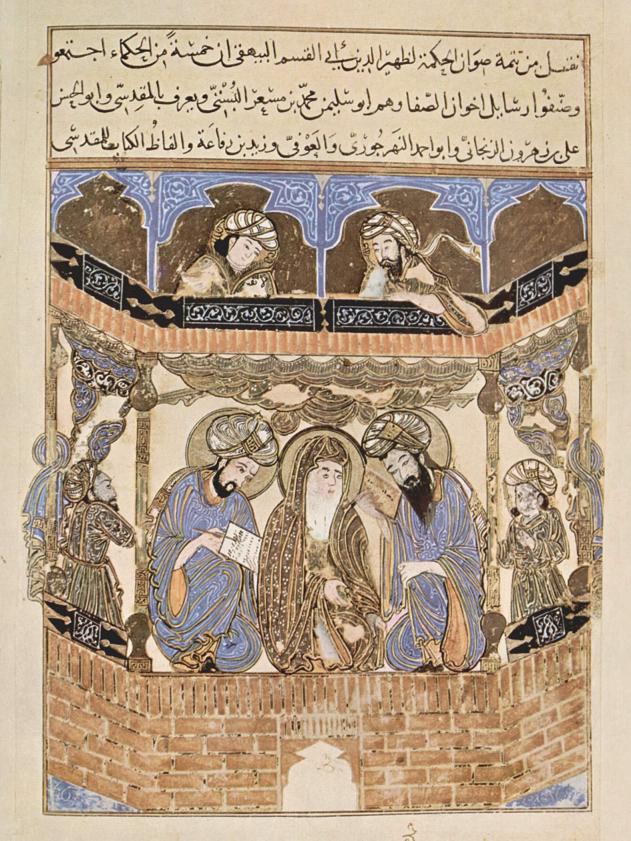

The image above is from a manuscript of the Rasa'il Ikhwan al-Safa dating from 1287 AD (Suleimaniye Library, Istanbul).

[1] Robert Irwin, ed., Night & Horses & the Desert: An Anthology of Classical Arabic Literature (NY: Anchor, 2001), p. 177.

[2] Ibid., p. 174.

[3] Ibid., p. 175.

.jpg)